The Gardener in the Machine: What Brian Eno Can Teach Us About the Future of AI

The Unseen Architect of the Digital Sound

Brian Eno has always operated just outside the spotlight. His influence is everywhere, yet rarely announced. He is best known as the father of ambient music, a genre designed not to demand attention, but to shape the environment in which attention unfolds. Music as atmosphere. Sound as context.

And yet, one of his most widely experienced works is not an album at all. It’s a sound most people barely noticed: the six-second startup chime of Windows 95. A fleeting moment. A threshold sound. A reminder that even the most functional systems carry emotional weight.

But Eno’s relevance today has less to do with music than with mindset. Long before “AI” entered the mainstream vocabulary, he was wrestling with the implications of generative systems, systems that produce outcomes without being micromanaged, that surprise their creators, that evolve over time.

In the 1970s, Eno began shifting away from composing songs and toward designing conditions. He stopped asking, What should this sound like? and started asking, What rules would allow something interesting to emerge? That shift, from creator to system designer, turns out to be one of the most useful lenses we have for understanding large language models today.

If we want to navigate a world increasingly shaped by AI, we don’t need more certainty. We need better metaphors. Eno offers one.

From Architect to Gardener: A New Paradigm for Creation

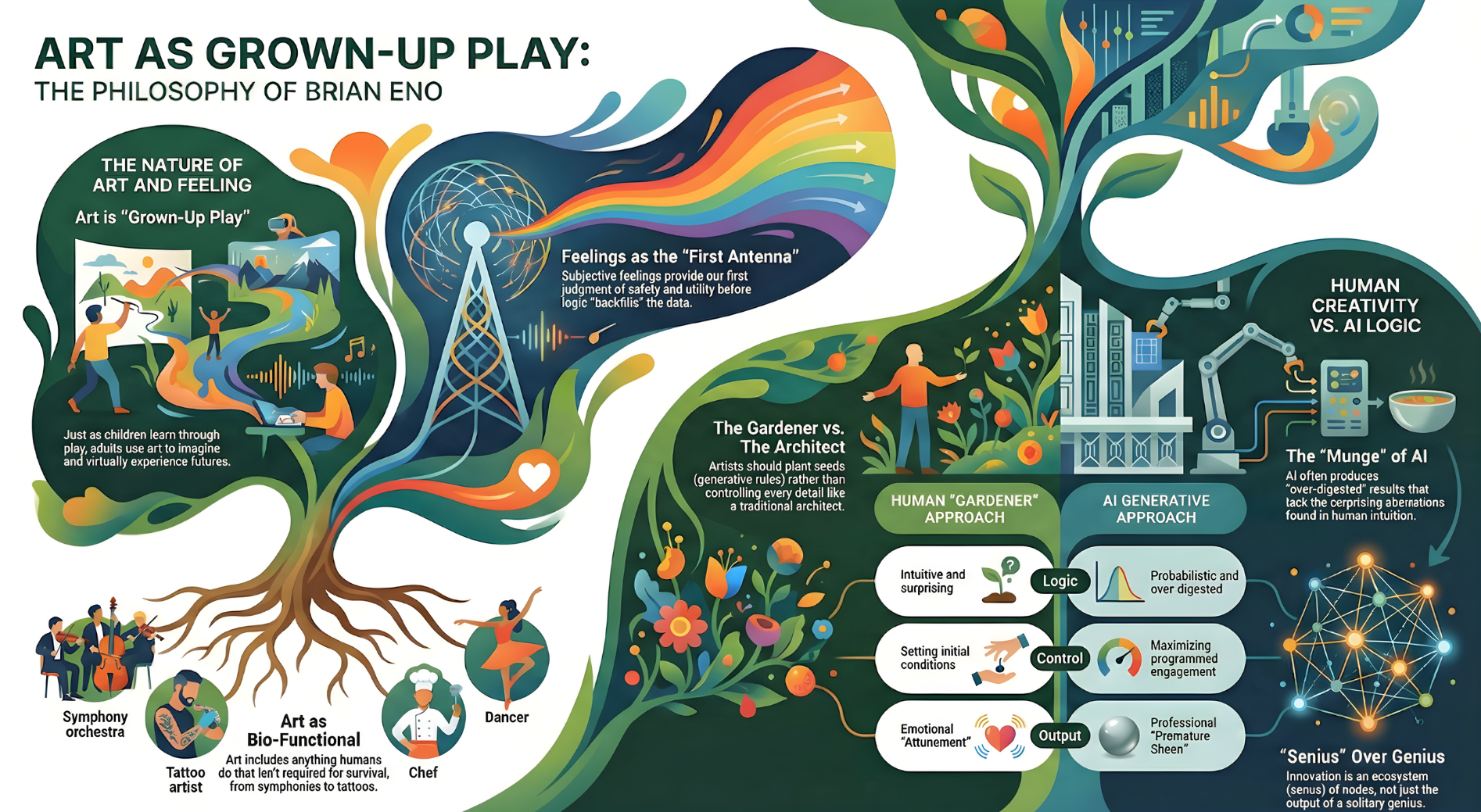

Eno draws a sharp distinction between two modes of making: the architect and the gardener.

The architect designs from the top down. Every detail is planned in advance. Frank Lloyd Wright, whom Eno often cites, famously designed not just buildings but furniture, cutlery, everything. The work is complete before it’s ever built. Execution is merely translation.

Generative systems don’t work this way.

In a generative model, control is distributed. The creator becomes a gardener, someone who plants seeds, defines constraints, and then observes what happens. Growth is shaped, not dictated. The outcome is not a single object, but a field of possibilities.

Eno describes art not as a finished thing, but as a “package of possibilities.” That idea borrows directly from Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn, where Brand notes that buildings aren’t static. They adapt, degrade, and evolve. “You never finish a building,” Brand writes. “You only start it.”

The same is true of generative systems. You don’t complete them. You initiate them.

This has profound implications for AI. The real work is no longer in refining outputs, but in designing conditions, training data, constraints, incentives, that allow a system to evolve in useful ways. Mastery shifts from precision to stewardship.

The Power of “Senius”: AI as a Collective Ecosystem

One of Eno’s most quietly radical ideas is his rejection of the lone genius myth. In its place, he offers “Senius,” a form of shared intelligence that emerges from a cultural ecosystem.

To explain it, Eno often points to the Russian avant-garde. Movements like Suprematism and Constructivism didn’t arise because of a single visionary. They emerged from a dense network of artists, critics, patrons, printers, teachers, and yes, cafés that let artists eat on credit. Innovation was communal infrastructure, not individual brilliance.

AI is Senius made literal.

A large language model is not an independent mind. It is a compression of collective human output, language, ideas, arguments, mistakes, captured and reassembled probabilistically. Its “intelligence” is not original. It is ecological.

Seen this way, AI doesn’t replace human creativity. It reflects it. It surfaces patterns already present in the culture. Progress, as Eno reminds us, is rarely a leap. It’s a marginal advance built atop shared groundwork.

Understanding AI as Senius shifts the question from What can the machine do? to What kind of culture are we feeding it?

Beware of “The Munge”: The Trap of Probabilistic Mediocrity

Eno is not naïve about generative systems. Alongside their promise, he warns of a subtle danger he calls “The Munge.”

The term comes from a childhood memory: a jar of watercolor rinse water that, after enough mixing, turns into a dull, purplish-brown sludge. Every color is technically present. None are alive.

AI produces Munge when it over-relies on frequency, when it averages culture instead of challenging it. The results feel polished, competent, and deeply unremarkable.

Eno likens early reactions to AI to Samuel Johnson’s remark about a dog walking on its hind legs. The marvel isn’t that it does it well, but that it does it at all. But once the novelty fades, what remains can feel like the work of a “dull human being.”

This is compounded by what architect Rem Koolhaas called “premature sheen.” Early computer renderings made everything look finished, regardless of quality. AI does the same. It adds gloss before judgment. Smoothness replaces substance.

What gets lost are the productive failures, the bent spindles. Eno’s own work is full of them. The famous “butterfly echo” came from a broken tape recorder. The mistake was the innovation.

Without room for error, AI risks becoming a factory for Munge, statistically impressive, creatively inert.

The Social Contract: Managing the Intellectual Commons

Because AI is built from socially produced material, Eno argues that it demands a new social contract.

These systems are trained on the accumulated output of humanity, our writing, art, conversations, and labor. When that collective resource generates private wealth, something is misaligned.

Eno suggests that a significant portion of AI profits, he floats 50 percent, should flow back to society. Not as charity. As royalties. A recognition that the value being extracted is communal.

This isn’t just a moral argument. It’s a practical one. If creators lose incentive to create, if everything they produce is simply absorbed into a system that benefits a few, the cultural ecosystem degrades. And when the ecosystem degrades, so does the model.

You can’t extract intelligence indefinitely without reinvesting in its source.

Art as Adult Play: Why We Need “Useless” Systems

At the core of Eno’s philosophy is a deceptively simple idea: art is biologically functional.

Children learn through play. Adults, Eno suggests, play through art.

Art allows us to rehearse emotional states. To inhabit worlds we don’t live in. To safely explore danger, power, loss, and control. It’s how we practice being human.

This is where AI becomes risky, not when it automates tasks, but when it replaces engagement. If we outsource journaling, reflection, and creative struggle to machines, we stop practicing. We stop playing.

Using AI as a tool is one thing. Hiring it to feel for us is another.

When creation becomes frictionless, imagination atrophies.

The Friction of Being Human

We are living in an age of presets. Of default answers. Of polished outputs delivered instantly.

And that is precisely the danger.

Innovation requires friction, the pause that lets us notice what’s happening, the resistance that allows correction. Eno captures our moment with a stark metaphor: we’ve built a car that can go 750 miles per hour, but we’ve skipped the brakes because they slow profits.

In a world where machines can generate answers endlessly, human value shifts. It lives in discernment. In noticing the small thing that matters. In welcoming the mistake that opens a new path.

The future doesn’t belong to those who surrender to the machine’s sheen. It belongs to the gardeners, those willing to work with uncertainty, to shape conditions rather than demand outcomes, and to stay present in the messy, unfinished process of becoming.

Because that friction?

That’s where being human still matters.